Have you ever had a moment where everything in your life lines up for a period of intense perfection? If not, I hope you do at some point. If you have, you know exactly what I’m going to write about.

I used to say that I never needed to drink or smoke or do anything crazy to stimulate myself because I get high on life. When I was a strange, chubby, and colorful preteen this happened all the time. Now, I get more of a constant undercurrent that keeps me going so I haven’t had to use that phrase for a long time. But tonight it is a hundred percent applicable. I am high on life. I just reached a life climax. Whatever you want to call it, it happened.

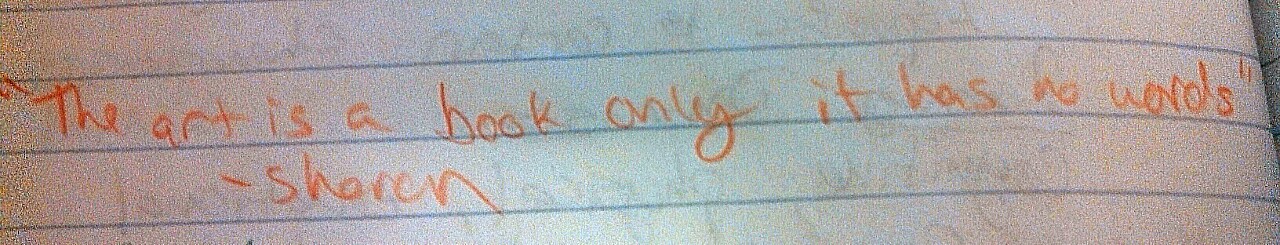

It all started with a few words thrown out by a third-grader named Shannon. “Art,” she said, “is a book only it has no words.” Although I was teaching at the moment, I broke out of that role, grabbed my notebook and the closest writing utensil (a bright orange colored pencil) and wrote her words down. Then I put my notebook aside and went back to teaching as if nothing had happened.

That class was on Wednesday and it was the first time I decided to have children explore the stories of art and then try to tell them. I started by asking the kids whether they thought art and stories were connected and, if they were, how. That’s when Sharon spoke up and started this whole adventure. We moved to round-robin drawing where we all sat in a circle and started a drawing. Then, after a minute, we passed our drawing on and everyone worked on someone else’s drawing and on around the table. Once we all got our own drawings back, I asked the kids to color in the drawings and make it their own again. Then we split into pairs and told the stories behind our new drawings.

If only you could have heard these children’s stories. A little girl with a cyclops named Eeeeeve (you have to do a dance when you say the name), a little boy with a woman who sailed away from home and out into the ocean to a place where all the colors changed and she turned pink, and another who recreated King Arthur with everything being metallic. Mine was called “How the eel got its electricity” since one child had drawn a lighting bolt striking a two-headed snake in the middle of what had become an ocean scene.

After that I gave the kids “Watson and the Shark,” a famous historic painting in the American section of the MFA. I told them to come up with the story for the painting and decide how to tell it while I went and waited on the other side of the room. Man oh man did they. Their brains were already going form their own stories and they just went wild on that old dry painting, bringing it to life in a way that I have never heard a tour guide manage to do.

Today I took another approach to the same teaching activity except instead of starting with them drawing I started by telling the story of, you guessed it, “Watson and the Shark.” The children from Wednesday had taught me that with a few pieces of historical information, a lot of guesswork, and some dramatic flair, I can bring any painting alive for children. And I did. Sitting in the slightly chaotic setting of a Boys and Girls Club I held up a laminated picture of Watson and the Shark and had every face turned to me, drinking in every word that John Singleton Copley painted into that painting in 1778.

Then I split the kids and told them that they were each going to get a painting. I exaggerated how they couldn’t look at anyone elses painting, making them close their eyes and sliding the painting reproductions face down across the tables. After that I sent the groups to separate corners of the room to decide what the story was in their painting and how they could show that story in a frozen sculpture. In graduate school, where I first heard the term “frozen sculpture” (or more technically, tableau) I was skeptical about whether kids would understand that.

There some adult person goes again, underestimating the enormous capacity held within children. Once I did a demonstration with them and we all froze in a position from “Watson and the Shark” they grabbed the paintings and ran. For the one or two children who didn’t get it I told them it was like pressing pause on the TV and seeing how the picture represents the movie. Immediate connection.

If only I could share the pictures I got today. Unfortunately rights and protection means that they have to stay for personal use, but I saw Edward Hopper, John Singleton Copley, and John Singer Sargent paintings come to life in front of my eyes. The children were incredible. I had each class put on a performance, introducing each group as a new act. They created sculptures, the audience guessed at the story, and the actors unfroze and told how they saw the story. Then the painting was revealed and minds were blown.

Today I realized something that has been causing me an undercurrent of discomfort. I don’t want to be an art teacher. I don’t have the skills or desire to teach the technicalities of drawing or painting. For a while this has been making me feel uncomfortable and like a sham of an art teacher. But this week I saw what I really want to teach. Not art techniques or drawing skills, my goal in life isn’t to train more artists. I want to teach how to recognize the importance of everyday stories. Or, to use other words, how to empathize.

When I heard these children talking I could feel their young minds being pulled by themselves, their interaction with each other, and their interaction with the art. They looked at an image and they connected to it. Today I had two ten year old Hispanic girls acting out Edward Hopper’s Room in Brooklyn and two more guessing the story. Both sets of girls decided, two from looking at the painting and two from looking at their friends frozen sculpture of the painting, that the woman depicted was sad because of the death of a loved one. Ten year olds!

After thirty five minutes I watched a group of children progress from “That’s a boring painting” to an in depth discussion about the clues in the painting and frozen sculpture that tell us that the woman is sad, perhaps because of the death of a family member. That, that, is why I want to teach. To encourage, through creating, discussing, and understanding art, a moment of true human connection. Because if a child can connect to a reproduction of a painted image of a woman sitting down, they can connect to and empathize with the child who is being bullied at school or the stranger crying on the bus. That human connection, through art to each other, from each other to art, is what I want to teach.

That is what can happen when art, people, and the connections between them come to light. When we learn to read art as the book with no words.